Bomi County – When Hawa Kromah was 11 years old, her parents wanted her to get education so they gave her to a lady only identified as Hadja. Hadja was a friend of her family.

Three years later, Hawa’s journey would take the wrong turn and she will end up becoming a 14-year-old wife of a 30-year-old man.

It was back in 2010, 11 year-old Hawa was the eldest of Famata and Alieu Konneh’s three children. They lived in Vorkor Town, Bomi County.

She helped her parents with household chores as there seemed to be no means of her going to school. So, when Hadja offered to take her to Monrovia to start school, her parents did not hesitate.

Hawa’s quest for education will shattered when she arrived in Monrovia. Hadja turned her over to Yamah Gayba. Instead of being a regular school-going kid, Yamah forced her into becoming a house maid.

“The day we arrived in Monrovia, I was taken to a woman named Aunty Yamah to help clean her home, wash clothes, and cook for them while her children went to school,” Yamah said.

“I had no time to rest; if I tried, she would beat me, denied me of eating and gave me extra work to do.”

Hawa’s ordeal became quite noticeable by Yamah’s spouse who opted that Hawa be given back to Hadja.

“Her husband was afraid that his wife would have gotten herself in a bigger problem,” she recalls during an interview with a LocalVoicesLiberia reporter.

“The day we arrived in Monrovia, I was taken to a woman named Aunty Yamah to help clean her home, wash clothes, and cook for them while her children went to school.” – Yamah Kromah, Victim of Human Trafficking

But Yamah later promise that she wouldn’t mistreat Hawa anymore and requested that the 11-year-old continued to stay with her.

But life will continue to be unbearable for Hawa. The violence and agrimony she endured became frequent.

“Whenever I made her angry, she would hit me and threatened to kill me if I reported her to anyone or decide to run away,” Hawa narrated.

“I started to demand that I go back to my parents. I wished that I had not come in the first place.”

As Hawa insistently continued her demand to be returned to her parents, Yamah then opted to send her away to a different place.

“She finally agreed to take me back and I was glad that for once she was going to do something with a good conscience. But it didn’t turn out as expected; instead of taking me back to my parents in the village she took me to Kpakar, another town in Bomi to live with her mom.”

“Life remained the same; I had no hopes of seeing my parents again. I could go on the farm every morning to work and get back to the village in the evening to get food prepared for the old ma.”

Hawa recalled how she attempted fleeing on several occasions but was returned to Yamah’s mother village.

Her dreadful experiences clouded her thoughts and she became susceptible to fear. She grew furious and disdainful of her life as the days went by. She said she couldn’t find a meaning to live and at once attempted suicide.

“She finally agreed to take me back and I was glad that for once she was going to do something with a good conscience. But it didn’t turn out as expected; instead of taking me back to my parents in the village she took me to Kpakar, another town in Bomi to live with her mom.”

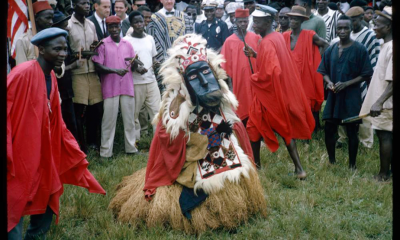

One day when Yamah returned to the village she forced Hawa into the Sande Society for the purpose of genital cutting.

“I fought and cried but I was helpless; the women were stronger than me and they overcame me,” she said with tears dripping from her cheeks.

Couple of months later, Hawa was saved. A family friend, who had recognized her, told her parents about her situation.

Famata, Hawa’s mother, was quick to intervene. Hawa was reunited with her parents and three siblings.

“I thought by allowing her to go with the woman she could prioritize the girl education to help society and Hawa’s life would’ve been changed and it could be different from mine,” Famata said through an interpreter. She recalled how she broke down in tears the day she saw her daughter in the village.

“I wanted justice. The elders and chiefs got involved and it was resolved through dialogue. Now, I am still in pain and I don’t know what to do because my daughter’s life is already messed up.”

Although she was not given justice, Hawa was upbeat for reuniting with her family. However, she still lives with the scar of her ordeal. She says she often has nightmares and flashbacks of the dreadful incidents of the past.

After she returned to her family, they were feeling the pinch of the challenging economy. Her mother and father were unable to put food on the table or pay their school fees.

So, Hawa was sent to her Uncle – Famata’s brother known as John. John offered to give Hawa education but he too has a large family and catering to their needs was a massive task as well.

“I would go to school one semester and drop out the next semester because of the lack of school fees. My uncle was also struggling. I felt like a burden on him,” she remembered.

Hawa’s last option, her parents thought, was to give her hand in marriage.

“It seemed like the only means of survival, so I couldn’t reject it. I have already been through a lot, so I could stand that. I was pushed against the wall. I felt like by that I would have lessened the burden on my family shoulders when I get marry,” Hawa said.

At 14, Hawa’s wedding was planned and her incoming husband was Haji Kromah, a 30-year-old local tailor and businessman.

By then Hawa had already concluded that her dream of getting education was ruined; so, she had to fulfill her duties as a house wife.

Now, Hawa is 22 and a mother of three children: Mariama, 4, Musa, 2, and 11-month-old Kadija.

“I want my children to acquire education. I don’t want them experiencing what I’ve experienced. I’ll never give my kids out to live with strangers,” Hawa said.

Aria Deemie is a practicing Liberian journalist, who is studying social work at the Mother Patern College of Health Sciences in Monrovia. She has acquired training from the SheWrites; SheLeads journalism mentorship program and LocalvoicesLiberia Media Network. Aria seeks to bring to light issues that have been withheld in the dark. She hopes to speak to the conscience of perpetrators of human rights abuses through her reports.

Methodology

True

The claim is rigorous and the content is demonstrably true.

Half True

The statement is correct, although it needs clarification additional information or context.

Unproven

Evidence publicly available neither proves nor disproves the claim. More research is needed.

Misleading

The statement contains correct data, but ignores very important elements or is mixed with incorrect data giving a different, inaccurate or false impression.

False

The claim is inaccurate according to the best evidence publicly available at this time.

Retraction

Upon further investigation of the claim, a different conclusion was determined leading to the removal of the initial determination.

Toxic

A rude, disrespectful, or unreasonable comment that is somewhat likely to make you leave a discussion or give up on sharing your perspective. Based on algorithmic detection of issues around toxicity, obscenity, threats, insults, and hate speech;